|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

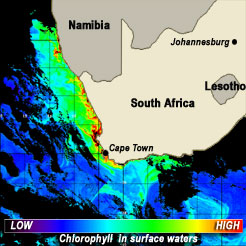

TOXIC DINOFLAGELLATE &

DIATOM BLOOMS

|

| Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (PSP) |

|

|

- Organisms impacted by

PSP in this area include white and black mussels, anchovy, herring,

mackerel, and sardine. Toxins may also be transferred through

the food web to whales and seals. In March 1980, approximately

5 million white mussels were washed ashore at Elands Bay after

becoming toxic from an Alexandrium catenella bloom.

- An interesting feature about PSP in South Africa

is that their abalone industry is being threatened. This is perplexing

because abalone are not known to be filter feeders and do not

graze microalgal cells. Instead they feed on kelp. Research is

underway to determine how the abalone are picking up the PSP toxins.

One thing that is known is once the abalone acquire the toxins,

they do not get rid of them quickly. It may take up to a year

for abalone to be eaten safely. This ability to retain toxins

is similar to the butter clam found off of Alaska's coast.

|

|

|

| Diarrhetic

Shellfish Poisoning (DSP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neurotoxic

Shellfish Poisoning (NSP) |

|

- The dinoflagellate Gymnodinium cf. mikimotoi

is present on the southern coast of South Africa and blooms frequently

in False Bay. This species causes NSP symptoms similar to those

reported during Gymnodinium breve blooms off the Florida

coast.

- Problems associated with these blooms include

skin and respiratory irritations.

- In 1989, 30 tons of abalone were killed on the

South Coast after a G. mikimotoi bloom.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

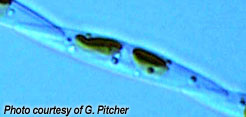

| Amnesic

Shellfish Poisoning (ASP) |

|

- This illness has not yet been reported in South

Africa

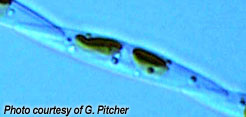

- However, the diatom responsible for ASP in other

regions, Pseudo-nitzschia sp., is present along certain

areas of the coast (see microscope image at right, >>).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HARMFUL (non-toxic) BLOOMS

|

|

|

| Brown

Tides |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

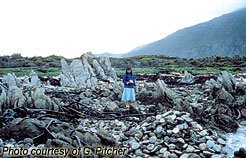

| Hydrogen Sulfide Poisoning |

|

- In March 1994, St. Helena Bay on South Africa’s

West Coast experienced a massive marine mortality.

- The event was caused by the decay of

a huge red tide of non-toxic dinoflagellates (dominated

by Ceratium furca and Prorocentrum micans).

- About 60 tons of rock lobster and 1500 tons

of fish were washed ashore.

- The lobster and fish died from suffocation and

hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Oxygen concentrations were near zero

and hydrogen sulfide concentrations were in excess of 50 micromols

per liter!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anoxia |

- In 1997 there was a massive bloom of the dinoflagellate

Ceratium furca in Elands Bay on the West Coast.

- When the bloom decayed, bacterial consumption

drastically reduced oxygen levels. Oxygen concentrations were

so low that over 1500 tons of rock lobster became stranded on

the beach and died.

- Anoxic events may lead to hydrogen sulfide poisoning

as the bacteria begin to use sulfur when oxygen isn’t available.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Red

and Black Tides |

- Red tides are

common along the South African Coast and are caused by a variety

of species. Some are harmful or toxic, while others are not.

- Noctiluca scintillans is one of the

many species in this region to form red tides. This species

is not toxic; however, it may cause fish mortalities when

blooms decay producing high ammonia levels.

- Mesodinium rubrum, a photosynthetic

ciliate, also discolors the water and appears purple or wine

colored. It is not toxic, although it has been associated

with faunal mortalities during bloom decay in St. Helena Bay

(described above). This species is one that performs diel

(i.e., daily) vertical migration making the red tide apparent

only during certain parts of the day.

- Diel vertical migration is a behavior characteristic

of algae that have the capability to swim (e.g., dinoflagellates).

They spend part of their time in the surface waters, photosynthesizing

where light is available. At night, these organisms can swim

down toward higher nutrient concentrations. This behavior

can determine whether or not a red tide is visible.

- Ciliates may form a bloom below the

surface waters even though the water color doesn’t

appear red. As the ciliates swim back to the surface in

the middle of the day, the red tide can re-appear.

- Black tides were observed in St. Helena Bay during the hydrogen sulfide poisoning

event in 1994 (described above). In this case, all of the light

entering the ocean was absorbed by the particles and dissolved

material in the water associated with the bloom.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fish

Kills: Chaetoceros- or Heterosigma-related |

- Although species of Chaetoceros and Heterosigma

are present in South African waters, there have been no reported

fish kills associated with these blooms.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|